Paul Pry - Broken Seals 3

01. May. 2006

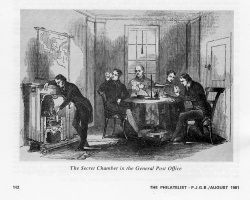

"The Secret Office" as imagined by the London Journal (15th March1845): A secretary looks through a sealed letter to get a glimpse of suspi-cious contents, thereafter the seal is copied by the man at the machine (by the "hammer method") before it is heated by the oven whilst the last person writes a copy.

In the autumn of 1844 a new type of letters emerged in the British post offices, sealed with wafers featuring crocodiles, clenched fists, and stinging bees, pointed at any unauthorized snooper - "Paul Pry" - at the post office who might think of opening the letter.

Political Scandal

It all started when Italian political refugee Guiseppe Mazzini had found a large number of his letters opened. Suspicion fell immediately on the British postal service and via left-wing Member of Parlia-ment T.S. Duncombe he had the matter brought up in Parliament in June 1844. It provoked howls of indignation in the newspapers. Great Britain had proud traditions of housing political refugees ir-respective of conviction, and the letter-opening violated one of the fundamental values of British self-esteem. The arrogant and dismissive behavior of the unpopular Secretary of State, James Gra-ham, did not make things better. After a couple of weeks he was forced to set up two investigation committees, one in each Chamber. The British postal espionage had to be ransacked.

Paul Pry envelope. In the middle an allegory of Great Britain with a small snake with "Sir James" head wriggling at the bottom. On the sides a busy Paul Pry.

Thorough Investigation

The reports were presented already in the begin-ning of August. The one from the House of Lords was only three pages establishing that the letters had been opened according to statutory orders from Graham, whereas the House of Commons in their report looked into the historical basis of the law that allowed the Secretary of State to issue orders for secret opening of letters. The report of more than 100 pages substantiated that postal espionage was at least as old as the postal service itself and it supported the Government in its recom-mendations: In certain cases postal espionage had helped the government to get better insight in the actual proportions of conspiracies which had led to a more moderate display of force. Total abolition would give criminals and enemies of the state a free rein; on the other hand, unconcealed censorship of letters would make criminals communicate through other channels. The dilemma is still well-known. The committee therefore recommended moderate employment: The best way intended to restrain the evil-minded from abusing the postal service is to "let it remain a mystery whether this force is still being practiced", was the somewhat contradictory conclusion of the committee.

Conspiracy Theories and Anger

The critics of the Government in Parliament and in the press were not impressed with the committees which they considered to be Graham's puppets. The public was fascinated and repelled. Conspiracy theories took over. The newspapers boosted with imaginative descriptions of secret postal espionage offices and stories of abuse. Some thought that breadcrumbs dipped in rubber water were a means to cast seals, others leaned towards the theory of a hammer beating small lead plates on the seals in this way making signets for re-sealing. Rumours had it that postmen had been seen with stains of sealing wax on their uniforms when delivering letters to people because the post spies had not had the time to let the sealing wax dry. Or nosy female post office employees in the country who kept regu-lar collections of seals with hearts and arrows in order to snoop into "little secrets".

Leader writers thundered and in the hullabaloo they appealed to the proud conceptions of liberal values on which the British society had been founded: Espionage was "extremely repellent to British feelings" a foreign (French resounding) word and it was an act that belonged among "the reptiles" in Vienna and St. Petersburg. The violation of the sacred private correspondence was "one of the most repulsive, dirty, and dishonourable acts that one could be guilty of". Postal espionage corrupted its performers - and who should look after them? It was like "some infectious pollution" of moral.

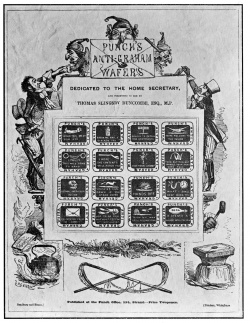

"Anti-Graham-wafers". In the middle of the 19th century adhesive envelopes were still rare and sealing wax was expensive. It was therefore not unusual the people closed their folded letters with wafers. Punch’s wafers were provided with effects and small humorous texts stipulating what would happen to any unauthorized person who opened the letter.

Crocodiles, Lobsters, and other Unpleasantness

The humorous paper Punch did even more harm, if possible, to the government's shifty reputation when launching the comical "Paul Pry", a round-shouldered gentleman with a top hat who is prying into other people's letters. In July the paper intro-duced a sheet of "anti-Graham wafers" supposed to stick to anyone who violated the letter, and an "anti-Graham envelope" with pictures of Paul Pry to match. With "anti-grahamed" letters people should drown the postal service in suspicious mail and in this way short-circuit the system - just like the inter-net actions that took place a couple of years ago in the wake of the rumours that the U.S. Intelligence was prying into people's private e-mails. Thou-sands of activists provided their e-mails with as many "suspicious" words as possible in order to drown the American search machines in irrelevant information.

In winter 1845 the pressure on the government had become so massive that "The Secret Office" under the postal service was closed down. For many years, contrary to the big powers on the continent, England had only sporadic access to read people's letters.

Mazzini and International Politics

What the Mazzini case was actually about was only partly revealed; perhaps the details of the case would have changed the public opinion because correspondence between Austria-Hungary and Eng-land discloses that representatives from Vienna had asked Graham for help to unravel an invasion of Italy which Mazzini was participating in organizing. They feared that a large rebellion would trigger off a major war between Austria-Hungary and France which might involve England as well. James Graham believed until his death that he had been a credit to his country.

This is the third article in the "Broken Seals" series. The previous articles were published in Muse-umsPosten no. 3 and 4, 2005.

This article may be copied or quoted with MuseumsPosten, Post & Tele Museum as source.

Comment this article

Only serious and factual comments will be published.