Erlund's Ghost - Broken Seals 8

10. Feb. 2008

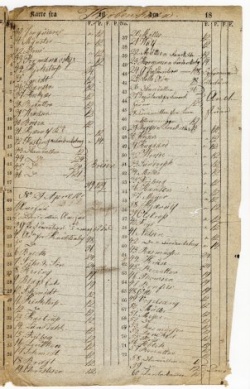

Letter Bill from Købmagergade post office of 29th April 1810.

In the summer of 1819 the name of Louis Pasavant featured on the so-called bill of letters that had arrived at the post office in Copenhagen by the mail from Hamburg. The bill - a list of all the recipients of letters - was hung up outside the post office enabling people to check if there were letters for them to collect.

Pasavant was probably an assumed name concealing the person Friedrich August Becker, a suspicious swindler, of whom the chief constable in Copenhagen, A.C. Kierulff, had been warned by a German colleague. According to the chief constable in Hamburg Pasavant had sent false notes of hand to an innkeeper in Copenhagen named Knirsch and later been trying to sell them to the commercial house of M. Mutzenbecher in Hamburg. Pasavant seemed to have disappeared from the face of the earth; it was only known from his letter to the commercial house, which had been sent from Copenhagen, that he had asked for a reply „auf hier Posterestance", i.e. to the post office in Copenhagen.

What only a few people knew was that the name on the bill covered a letter that did not even exist and that in the cellar beneath the post yard in Købmagergade a police officer was lying in wait in order to arrest the person that might appear to have the letter handed out; moreover, post office employee Stöcken, who was in charge of receipt and delivery of the letters from the post office, had been carefully instructed to try to delay the person long enough for another employee to fetch the policeman and, in case they did not make it, to have "Pasavant" shadowed by plain-clothes men.

Pasavant apparently avoided the trap, but the account proves that even in the early 19th century the postal service was ready for all sorts of things when it came to the safety of the realm. Prior to this there had been a very short correspondence between the postmaster-general and the chief constable in Copenhagen by which the postmaster-general had rejected the proposal from the chief constable that the postal service should make the arrest on their own. This would, he wrote, seem peculiar to the customers of the postal service and weaken their trust in the service. So much rather a little skulduggery.

Chief Constable Hans Haagen (1754-1815), undated.

The Postal Service versus the Police

The collaboration between the police and the postal service had started tumultuously twenty years earlier. In 1784, Crown Prince Frederik (later King Frederik the 6th) had repeated the ancient prohibition of letter-opening without special royal ordinance, and that was a principle which the postal service had chosen to follow.

When during the years from 1800 to 1803 the active chief constable Hans Haagen had repeatedly asked the postal service to surrender letters, the management of the postal service eventually chose to ask the government for advice.

The occasion was a case in 1803 when somebody had ordered stamped paper worth 640 rix-dollars from a vendor in Aalborg and asked for it to be sent to secretary Drieberg at the stamp office. The problem was, however, that this person did not exist; it was attempted fraud by abuse of stamped paper, and the chief constable therefore asked the General Directorate of Post to arrest the person that would come to collect the ordered papers. To have postal employees act as police officers was the straw that broke the camel's back as far as the postal service was concerned, and the request resulted in a protracted quarrel with the police.

Two Men Deceiving a Widow ...

The chief constable failed to understand why he was no longer allowed to seize letters when he could seize persons and other property. In one of his letters he described the instances where he had asked the postal service for help. One of the cases was about an unusually vile man by the name of Rose who had impregnated the widow of a tailor and whilst she was lying in childbed, he had run off for Hamburg together with a friend - and her entire fortune in bonds. The sly chief constable figured out that if the two fellows were as clever as they were black-hearted, they would send the bonds by mail to avoid the risk of being caught carrying them. Consequently, the postal service was instructed to intercept all letters addressed to the two villains. However, here he overestimated the impostors who were arrested in Schleswig with the bonds on them. But the story about the poor widow and the base scoundrels was good because it played on feelings, not only within the postal service, but also within the chancellery who followed the case closely.

The Post Office in Købmagergade, from the periodical Illustreret Tidende, 1880.

„An Unpleasant Odium"

Contrary to in Christian Erlund's days, however, the directors of the postal service considered it an "unpleasant odium [of „odious": something disagreeable, obnoxious]" to tamper with the letter seal and in doing so hazard the relationship of trust with the letter-writers that formed the basis of written communication. It all ended with a compromise to the effect that the postal service should hold back letters at the chief constable's request, but that it necessitated an approval from the chancellery to hand the letters over to him.

With the agreement between the police, the postal service, and the chancellery in January 1804 the independent role of the postal service in mail surveillance seemed to have had its day. During the war on England in 1807-14 the postal service managed to disclaim responsibility for the introduction of ex-tensive censorship of letters. The mail surveillance passed to the police who began to realize the potential of the secret letter-opening.

Erlund's Ghost

The ring was almost closed in 1820 when burgomaster and recorder (and thereby supreme police authority) in Holbæk, Frederik Ludvig Bierfreund wrote to the chief constable and suggested him to spy against the letters of some local suspected democrats. It should not prove too difficult, he wrote, for he had read about Christian Erlund's methods in Ove Malling's book on „Great and Good Deeds by Danes, Norwegians, and Holsteiners" from 1777. The ghost of the old postal controller lived on even after having relinquished his hold of the postal service.

This article may be copied or quoted with MuseumsPosten, Post & Tele Museum as source.

Comment this article

Only serious and factual comments will be published.